Image: ln24SA

THE EXTRICATION OF AFRICA FROM DETRIMENTAL TREATIES AND ORGANISATIONS

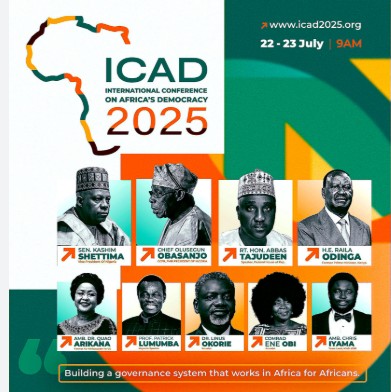

“The Developments from ICAD 2025”. To begin with, I’d like to make reference to a panel discussion moderated by LN24 International’s Yvonne Katsande. She was joined by Ambassador Dr Arikana, the former AU ambassador to the US, as well as Professor Patrick Lumumba, who is a lawyer and advocate, as well as the former director of the Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission. And right at the commencement of the panel discussion, Yvone Katsande poses a question that addresses one of the most critical focuses for the African continent, which is the subject of extrication from detrimental treaties and organisations. In responding to the question on how African countries can accomplish this, Ambassador Dr Arikana brought to mind something quite important. She states that we first need to have an accurate understanding of why international organisations like the UN, IMF and WB were created, and why that does not align with the best interests of Africa. She states that these institutions were formed after WWII when the Western World had destroyed itself again, and they needed systematised ways to justify plunder.

This immediately brought to mind what Professor Patrick Lumumba highlighted in his keynote address before the panel discussion, which is that neo-colonialism poses a threat far greater than colonisation itself, because this time around the colonial actors are faced with desperation – which we highlighted is due to the fact that Europe is spent – they do not have an abundance of resources that offer them a comparative advantage in global trade. And so, in the post colonial and post WWII era, neocolonists created international organisations that technically respect the provisions of laws and treaties that demand a respect for human rights and sovereignty in Africa, BUT that simultaneously create a legal justification for plunder.

And before we delve into manifestations of this legal justification for plunder, let’s revisit the moment where the President of Loveworld Incorporated highlighted the reality of Africa being the new world, where new resources are being discovered even now, while Europe is spent.

INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS: A NEOCOLONIAL MODEL FOR LEGALLY JUSTIFIED PLUNDER

So, let’s talk about international organisations as a neo-colonial model for legally justified plunder; and we ought to begin with the Bretton Woods institutions: being the WB and the IMF – in light of Structural adjustment policies. Now, structural adjustment policies were developed by two of the IMF and the World Bank. After the run on the dollar of 1979–80, the United States adjusted its monetary policy and instituted other measures so it could begin competing aggressively for capital on a global scale. This was successful, as can be seen from the current account of the country’s balance of payments. Enormous capital flows to the United States had the corollary of dramatically depleting the availability of capital to poor and middling countries. Giovanni Arrighi has observed that this scarcity of capital, which was heralded by the Mexican default of 1982, created a propitious environment for the counterrevolution in development thought and practise that the neoliberal Washington Consensus began advocating at about the same time. Taking advantage of the financial straits of many low- and middle-income countries, the agencies of the consensus foisted on them measures of “structural adjustment” that did nothing to improve their position in the global hierarchy of wealth but greatly facilitated the redirection of capital flows toward sustaining the revival of US wealth and power.

Structural adjustment policies, as they are known today, originated due to a series of global economic disasters during the late 1970s: the oil crisis, debt crisis, multiple economic depressions, and stagflation. These fiscal disasters led policy makers to decide that deeper intervention was necessary to improve a country’s overall well-being – this was a big mistake.

Now, Mexico was the first country to implement structural adjustment in exchange for loans. During the 1980s the IMF and World Bank created loan packages for the majority of countries in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa as they experienced economic crises. To this day, economists can point to few, if any, examples of substantial economic growth among the LDCs under SAPs. Moreover, very few of the loans have been paid off. Hence, pressure mounts to forgive these debts, some of which demand substantial portions of government expenditures to service. In addition, there are multiple criticisms that focus on different elements of SAPs. There are many examples of structural adjustments failing. In Africa, instead of making economies grow fast, structural adjustment actually had a contractive impact in most countries. Economic growth in African countries in the 1980s and 1990s fell below the rates of previous decades. Agriculture suffered as state support was radically withdrawn. After the independence of African countries in the 1960s, industrialization had begun in some places, but it was now wiped out. In any case, let’s look at these criticisms in greater detail.

THE APT CRITICISMS OF STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT PROGRAMMES

First is the undermining of national sovereignty. More specifically, critics claim that SAPs threaten the sovereignty of national economies because an outside organisation is dictating a nation’s economic policy. One of the core problems with conventional structural-adjustment programs in this respect is the subsequent disproportionate cutting of social spending that is then mandated by structural adjustment programmes. When public budgets are slashed, the primary victims are disadvantaged communities who typically are not well organised. An almost classic criticism of structural adjustment is pointing out the dramatic cuts in the education and health sectors. In many cases, governments ended up spending less money on these essential services than on servicing international debts.

The second criticism is concerns Neo-colonialism and neo-imperialism. Concerning this, SAPS are viewed by some postcolonialists as the modern procedure of colonisation. By minimising a government’s ability to organise and regulate its internal economy, pathways are created for multinational companies to enter states and extract their resources. Upon independence from colonial rule, many nations that took on foreign debt were unable to repay it, limited as they were to production and exportation of cash crops, and restricted from control of their own more valuable natural resources (oil, minerals) by SAP free-trade and low-regulation requirements. In order to repay interest, these postcolonial countries are forced to acquire further foreign debt, in order to pay off previous interests, resulting in an endless cycle of financial subjugation.

Furthermore, Osterhammel’s The Dictionary of Human Geography defines colonialism as the “enduring relationship of domination and mode of dispossession, usually (or at least initially) between an indigenous (or enslaved) majority and a minority of interlopers (colonisers), who are convinced of their own superiority, pursue their own interests, and exercise power through a mixture of coercion, persuasion, conflict and collaboration”. The definition adopted by The Dictionary of Human Geography suggests (correctly so) that Washington Consensus SAPs resemble modern, financial colonisation!

Then there is Austerity. Critics hold SAPs responsible for much of the economic stagnation that has occurred in the borrowing countries. SAPs emphasise maintaining a balanced budget, which forces austerity programs. The casualties of balancing a budget are often social programs. For example, if a government cuts education funding, universality is impaired, and therefore long-term economic growth. Similarly, cuts to health programs have allowed diseases such as AIDS to devastate some areas’ economies by destroying the workforce. A 2009 book by Rick Rowden entitled The Deadly Ideas of Neoliberalism: How the IMF has Undermined Public Health and the Fight Against AIDS claims that the IMF’s monetarist approach towards prioritising price stability (low inflation) and fiscal restraint (low budget deficits) was unnecessarily restrictive and has prevented developing countries from being able to scale up long-term public investment as a percentage of GDP in the underlying public health infrastructure. The book claims the consequences have been chronically underfunded public health systems, leading to dilapidated health infrastructure, inadequate numbers of health personnel, and demoralising working conditions that have fueled the “push factors” driving the brain drain of nurses migrating from poor countries to rich ones, all of which has undermined public health systems and the fight against HIV/AIDS in developing countries!

THE HARMFUL IMPACT OF FOREIGN AID ON RECIPIENT COUNTRIES AND CITIZENS

Let’s also discuss foreign aid. The problem with foreign aid is notable in various contexts and performed by various actors. A high proportion of foreign aid is in the form of loans, which cripple developing countries through the accumulation of debt. Many rich nations receive more in interest payments from recipient countries than they give in “aid”. Especially since the 2008 financial crash, western governments have exploited their ability to borrow money at low rates by setting up aid programmes lending to poor countries at much higher rates, minting money on the backs of the poor. This is not aid, it’s a scandal. However, this problem is embedded in the very nature of humanitarian or foreign aid itself.

DEVELOPING DEMOCRACY: CHARTING AFRICA’S PATHWAY FROM NEOLIBERALISM AND EXPLOITATION

Let’s also talk about democracy, because it is a massive feature at ICAD – particularly, the idea of decolonising democracy. We are often told that democracy is the ideal system, the pinnacle of governance, really. But is it really suitable for every society, especially in Africa? This question becomes even more relevant when we consider how democracy has led to the rise of civilian governments that have been penetrated by neocolonial influences in many African nations, or even has amounted to a system where people vote based on religion or ethnicity rather than policies or capabilities. So, what is a well appropriated and commensurate adoption of democracy in Africa?

In Africa, the practice of a western liberal form of democracy has had its share of challenges. For instance, elections (while being crucial) have also brought civil unrest – so much so, that people anticipate unrest and violence, often staying home or leaving their towns during voting periods (hence the often concerning percentage of the population that commits to casting a vote). In addition, democracy has not always brought the peace it promises; instead, it has exacerbated divisions, particularly along ethnic and religious lines, as we see that at times, people in Africa vote for someone from their community or religion, not necessarily the most capable person to lead the country.

So, what’s the alternative? I think that there are tenets of democracy that are essential – like elections. But, we need to rethink how we select leaders. And the same way we require education and training to become a doctor or a teacher, there should be a process to vet and prepare individuals who aspire to lead a country. Leaders should have the capability, education, and (more importantly) experience and a track record of good works in leadership, in which they have advanced society.

Second, we need to move away from the idea of multiparty systems, especially in countries as diverse as those in Africa. Multiparty politics often exacerbate divisions rather than unify people. Instead, a single-party system with room for various ideas and solutions could provide a more cohesive structure. It is not practical for citizens to have to choose from 200 or 900 political parties. That is a pre-condition for coalition governance – because of course there will not be a clear majority!

Now, this is not to say that there must be a homogenisation of political parties – absolutely not! We need competition that creates an incentive to be the best at responding to the mandate for citizens. Rather, this is to say that the failure to conglutinate and work as one with people you align with, thus resulting in there being many parties, is an indictment on the political class. In fact, it already proves there is an incapacity to cooperate with others for the advancement of a country, and so, citizens cannot afford to trust you. So, these are some of the things that need to be corrected when it comes to how Africa appropriates democracy.

Written By Lindokuhle Mabaso

Get the latests of our Loveworld News from our Johannesburg Stations and News Station South Africa, LN24 International